13,491 reads

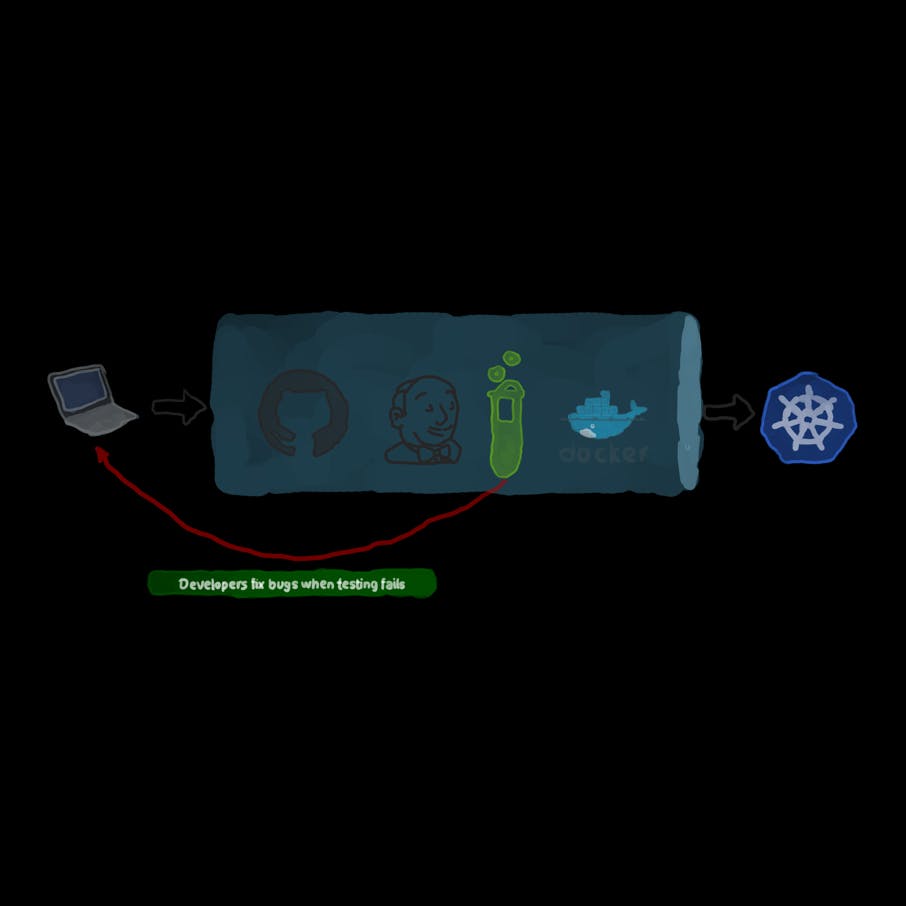

How To Create a CD pipeline with Kubernetes, Ansible, and Jenkins

by

March 1st, 2020

Audio Presented by

Right-size your Kubernetes, achieve better app performance, and lower your cloud infrastructure cost

About Author

Right-size your Kubernetes, achieve better app performance, and lower your cloud infrastructure cost