1,412 reads

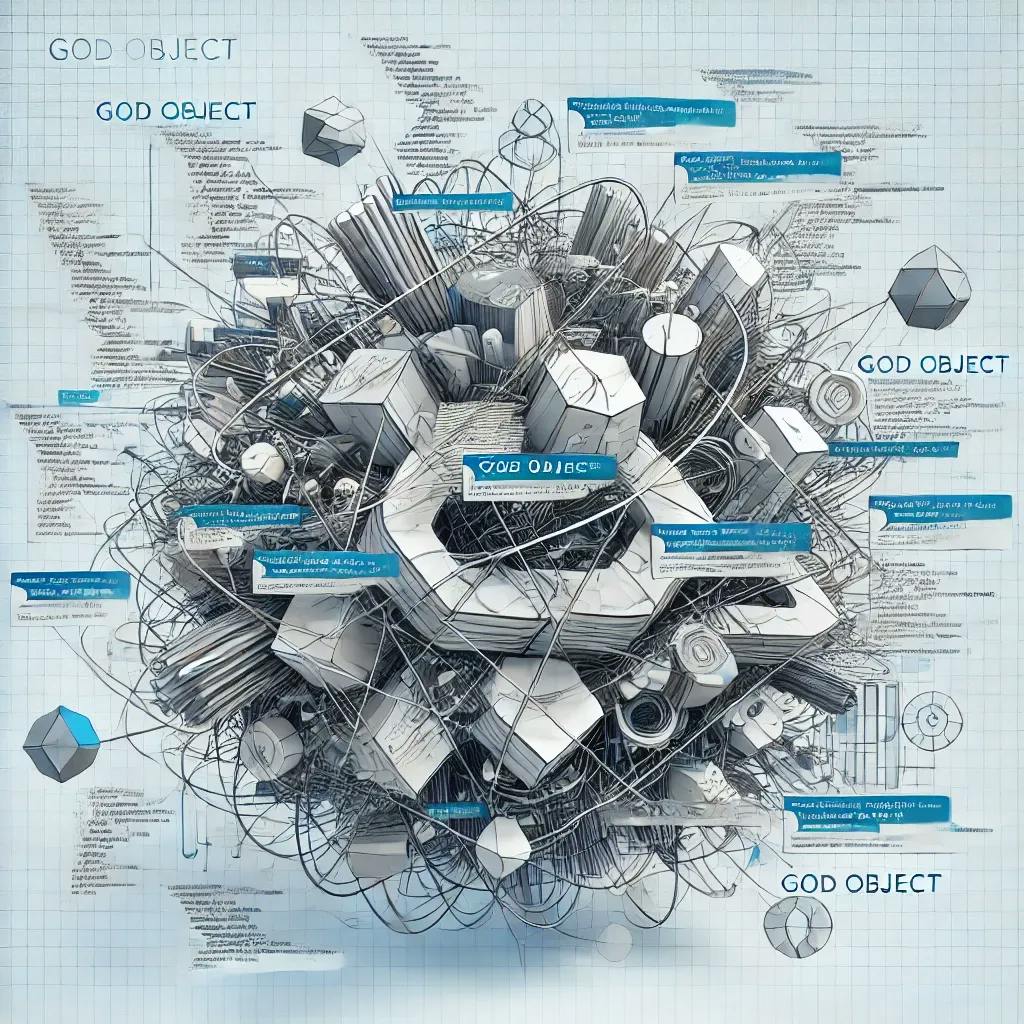

Avoiding Software Bottlenecks: Understanding the 'God Object' Anti-Pattern

by

November 29th, 2024

Audio Presented by

Highly skilled Application Architect with 17 years of experience in designing and implementing cloud-based solutions.

Story's Credibility

About Author

Highly skilled Application Architect with 17 years of experience in designing and implementing cloud-based solutions.