207 reads

An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding, Volume I: Book II, Chapter XXX.

by

August 3rd, 2022

Audio Presented by

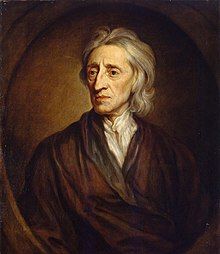

English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers

About Author

English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers