1,047 reads

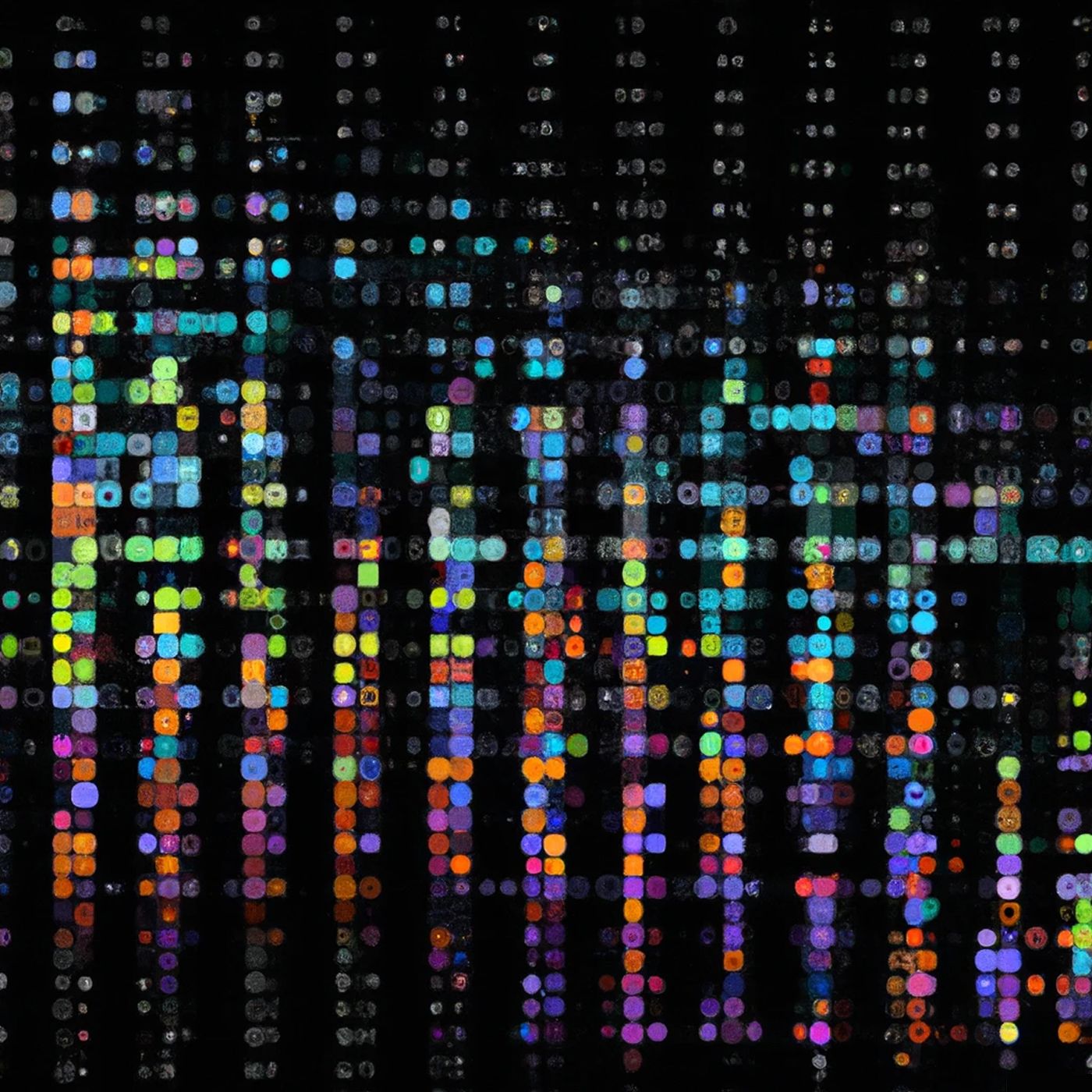

Music Generation Via A Hidden Markov Model - Part 1

by

July 30th, 2024

Audio Presented by

Speech and language processing. At the end of the beginning.

Story's Credibility

About Author

Speech and language processing. At the end of the beginning.