206 reads

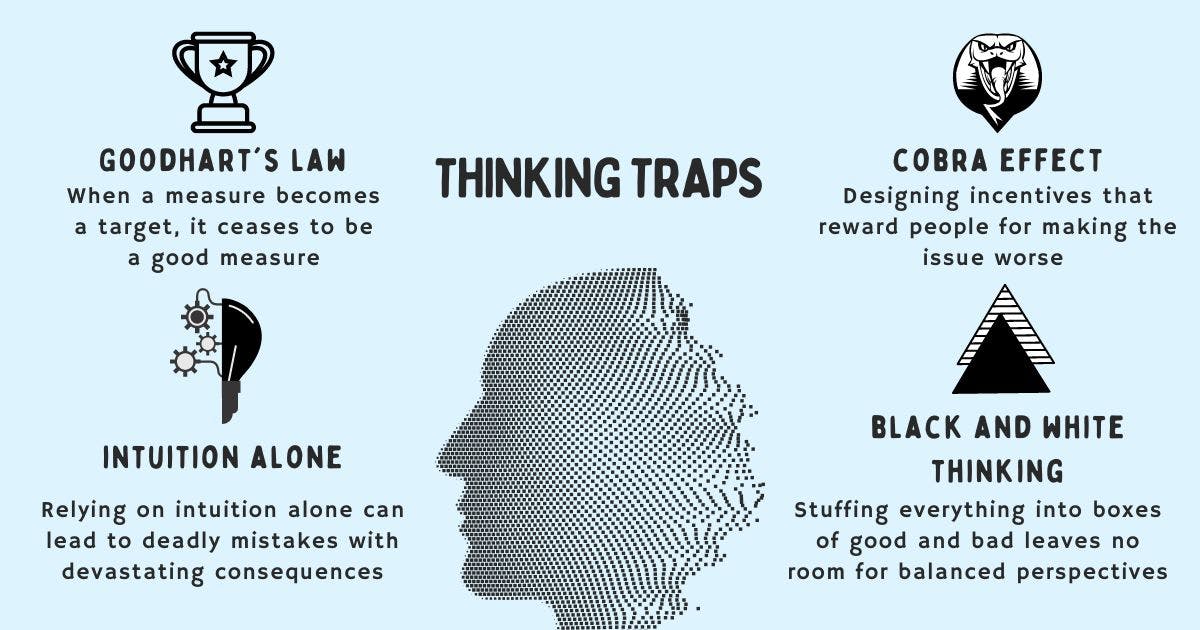

Liberate Yourself from These Four Traps of Leadership Thinking

by

August 24th, 2023

Audio Presented by

Author Upgrade Your Mindset, Rethink Imposter Syndrome. Scaling products → Scaling thinking. Former AVP Engg @Swiggy

Story's Credibility

About Author

Author Upgrade Your Mindset, Rethink Imposter Syndrome. Scaling products → Scaling thinking. Former AVP Engg @Swiggy