846 reads

Have You Read Your Privacy Notice in Detail?

by

October 19th, 2022

Audio Presented by

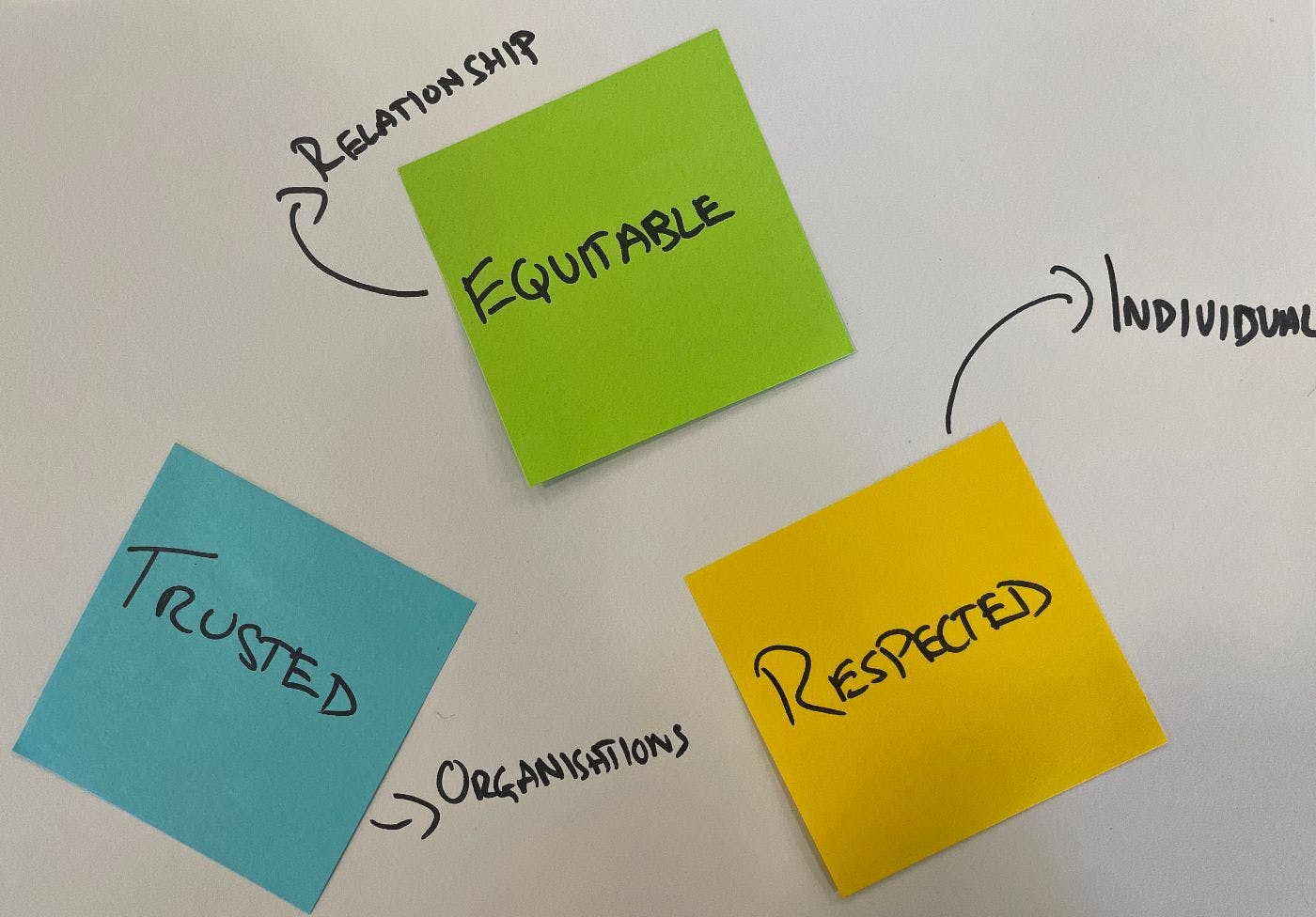

On a mission to create world where every piece of data is trusted, valued and never abused

About Author

On a mission to create world where every piece of data is trusted, valued and never abused