115,008 reads

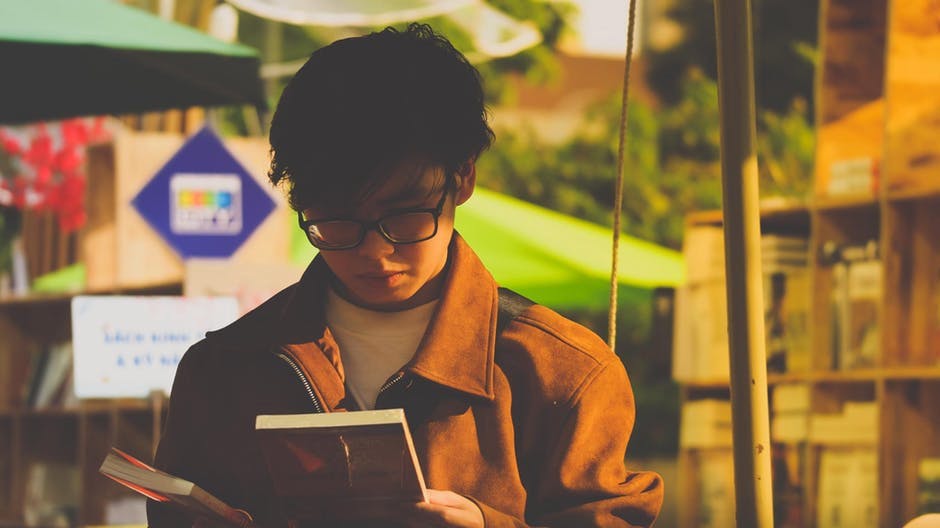

Everything I Knew About Reading Was Wrong

by

September 23rd, 2018

Audio Presented by

Writer, Programmer, Poker Player. I write on Books, Strategy, Decision Making, Psychology, Learning & Self Development.

About Author

Writer, Programmer, Poker Player. I write on Books, Strategy, Decision Making, Psychology, Learning & Self Development.