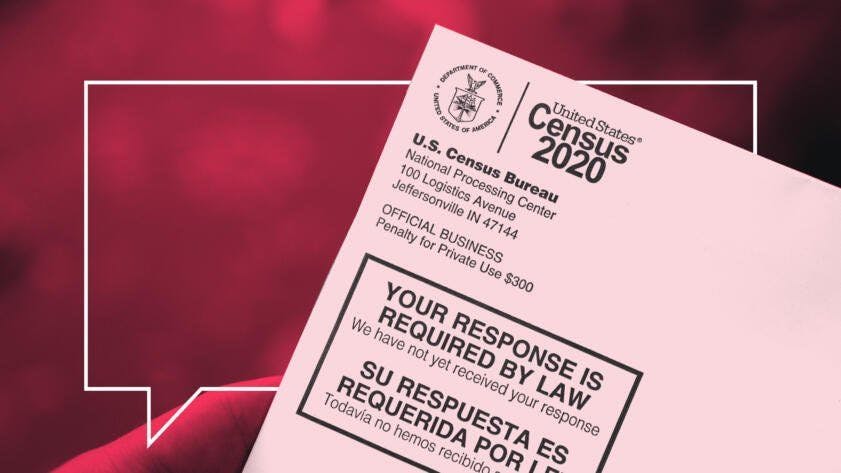

What Was Different About The 2020 Census And Its Challenges

by

June 19th, 2021

Nonprofit organization dedicated to data-driven tech accountability journalism & privacy protection.

About Author

Nonprofit organization dedicated to data-driven tech accountability journalism & privacy protection.