1,520 reads

What is (wrong with) software?

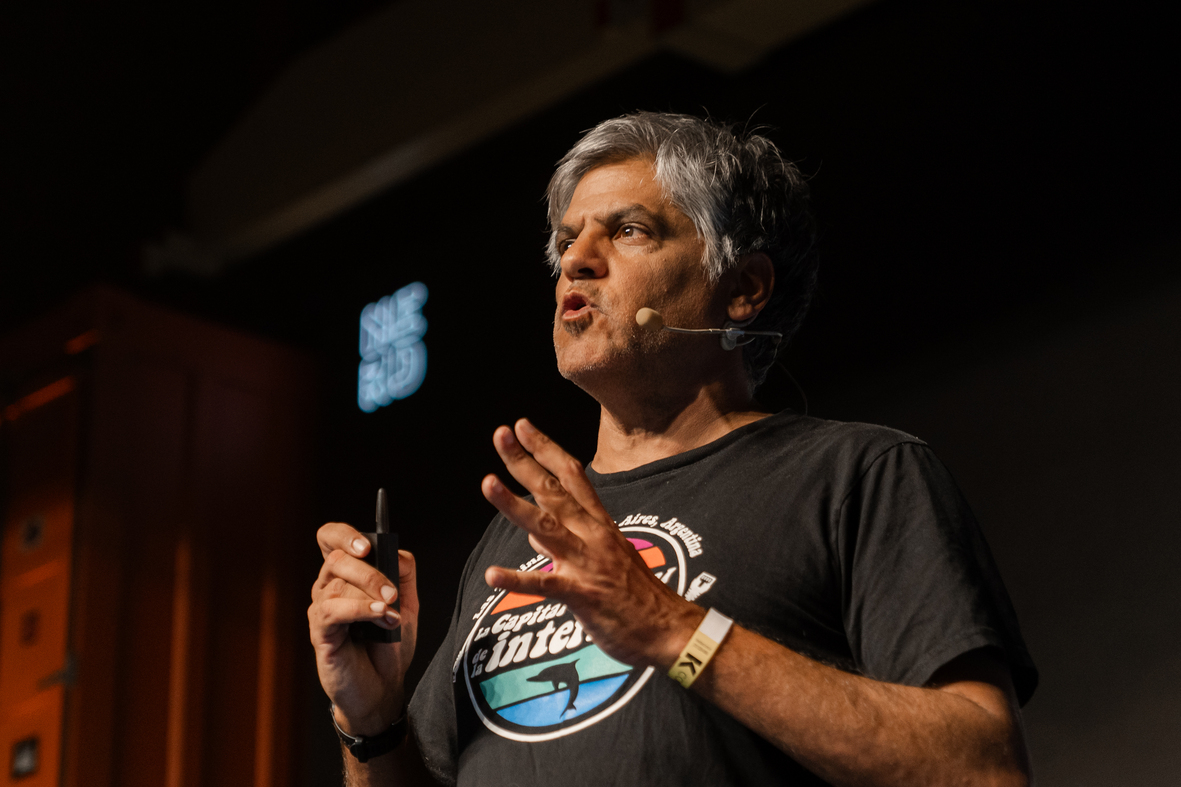

by

March 5th, 2020

I’m a sr software engineer specialized in Clean Code, Design and TDD Book "Clean Code Cookbook" 500+ articles written

About Author

I’m a sr software engineer specialized in Clean Code, Design and TDD Book "Clean Code Cookbook" 500+ articles written