1,273 reads

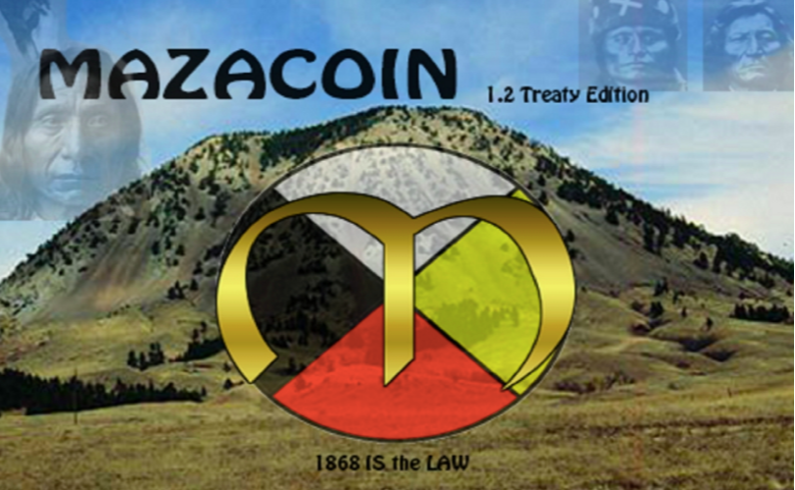

The Rise and Fall of a Tribal Cryptocurrency

by

September 6th, 2020

Audio Presented by

I am a researcher and freelance writer interested in new technologies that contribute to the social good

About Author

I am a researcher and freelance writer interested in new technologies that contribute to the social good