A description of the eye

Apr 13, 2023

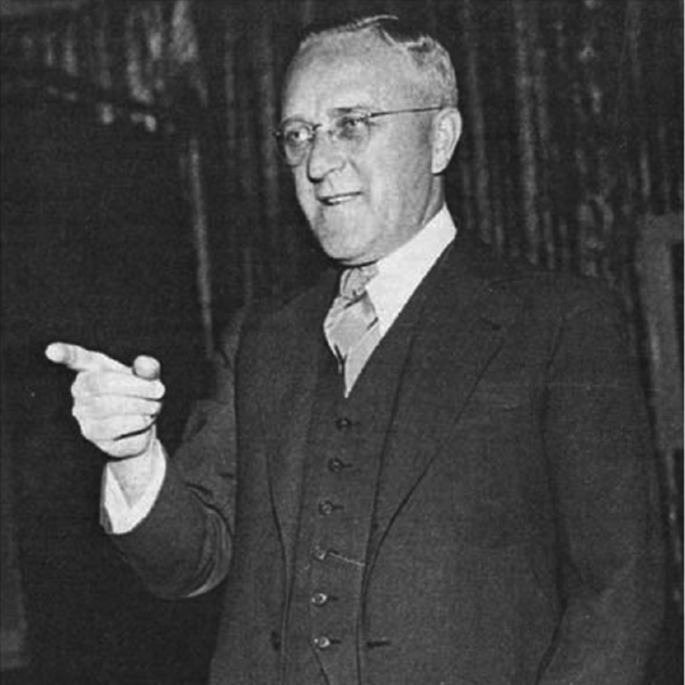

I was the Director of General Electric's Lighting Research Laboratory at its Nela Park National Lamps Works.

I was the Director of General Electric's Lighting Research Laboratory at its Nela Park National Lamps Works.

Apr 13, 2023

Apr 13, 2023