A Contribution to the Psychology of Rumour

Oct 06, 2023

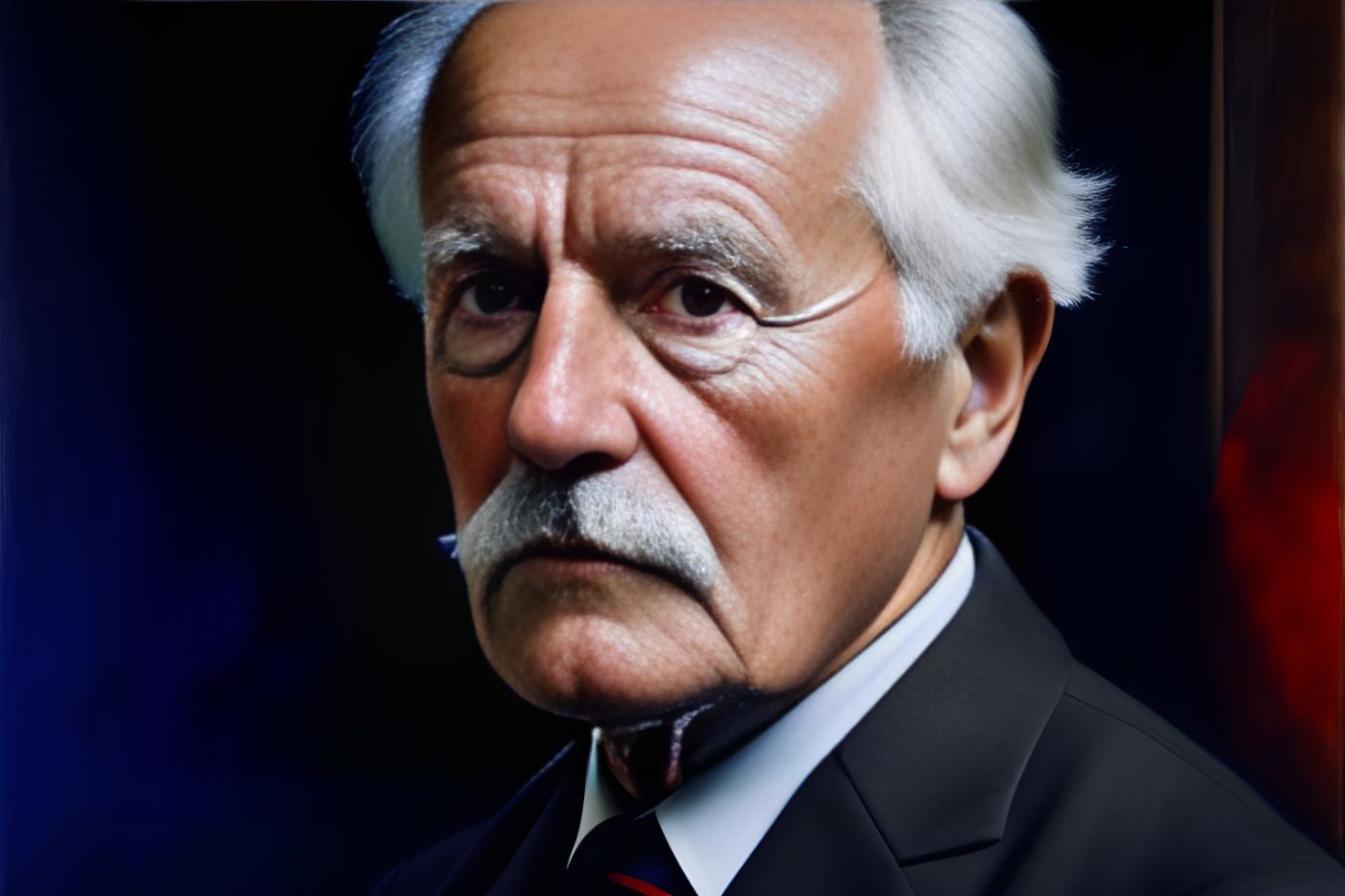

Carl Gustav Jung, Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst. Founder of analytical psychology.

Carl Gustav Jung, Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst. Founder of analytical psychology.

Oct 02, 2023

Sep 30, 2023

Oct 02, 2023

Sep 30, 2023