365 reads

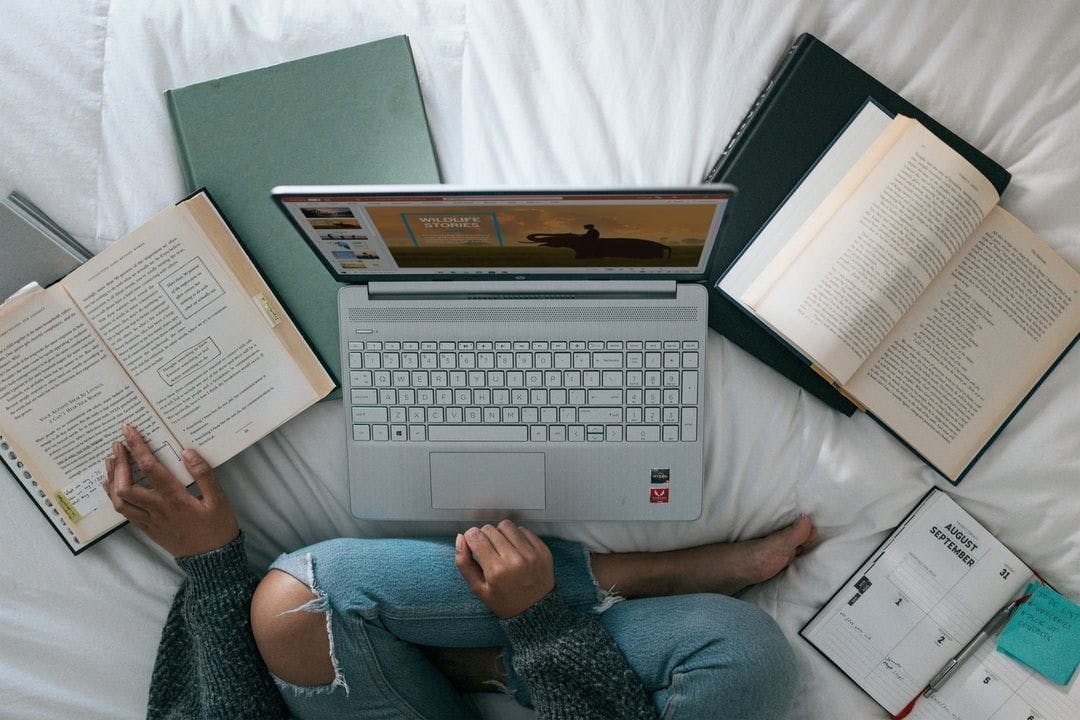

Mastering the Meta-Skill of Learning

by

October 30th, 2021

Audio Presented by

Web developer writing essays about mindset, productivity, tech and others. Personal blog: https://roxanamurariu.com/

About Author

Web developer writing essays about mindset, productivity, tech and others. Personal blog: https://roxanamurariu.com/