1,182 reads

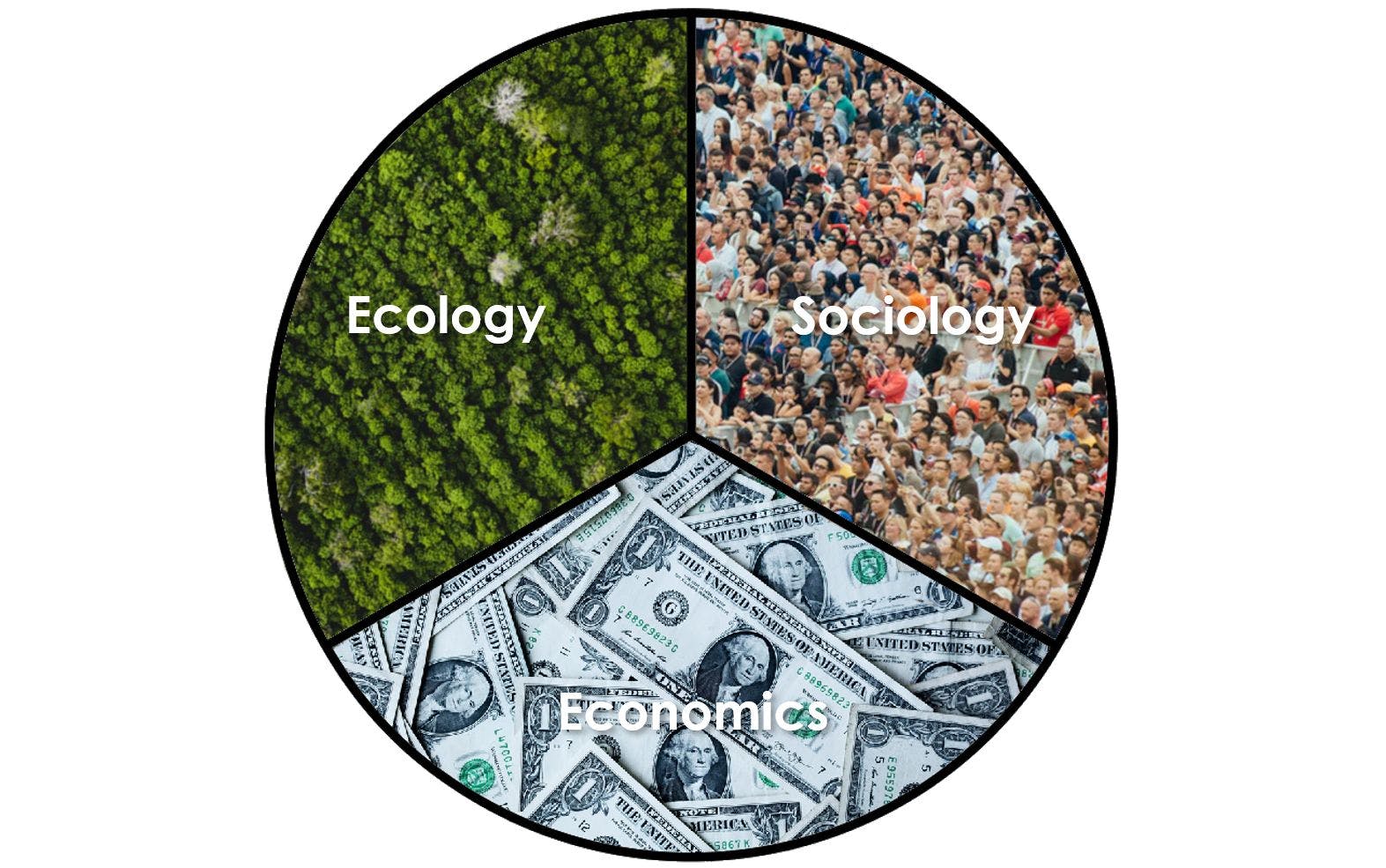

Introducing The Triple Layer Business Model Canvas

by

October 26th, 2021

Audio Presented by

Strategy Consultant | Tech writer | AI writer of the Year | Somewhat French

About Author

Strategy Consultant | Tech writer | AI writer of the Year | Somewhat French