526 reads

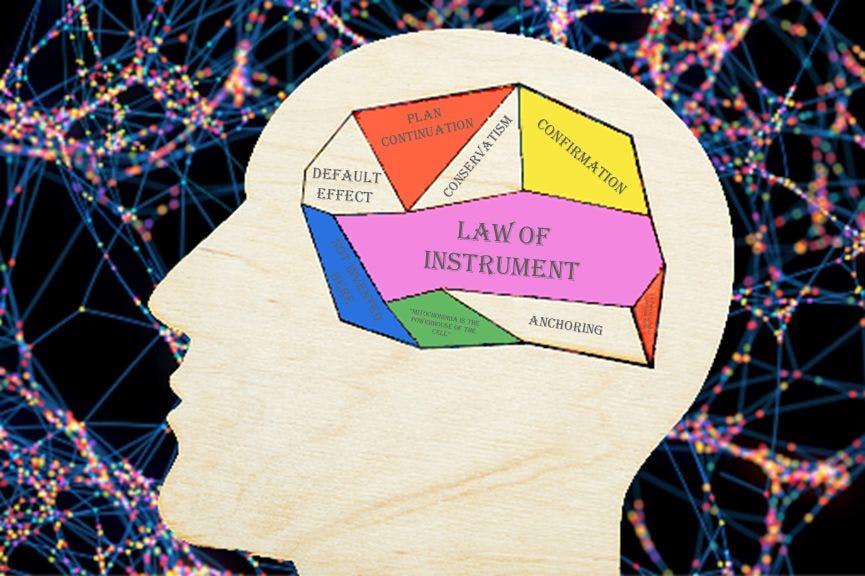

10 Logical Fallacies and Cognitive Biases Blocking Your Creativity

by

November 16th, 2021

Audio Presented by

Strategy Consultant | Tech writer | AI writer of the Year | Somewhat French

About Author

Strategy Consultant | Tech writer | AI writer of the Year | Somewhat French