Clocks and Foot Rules

Jun 02, 2023

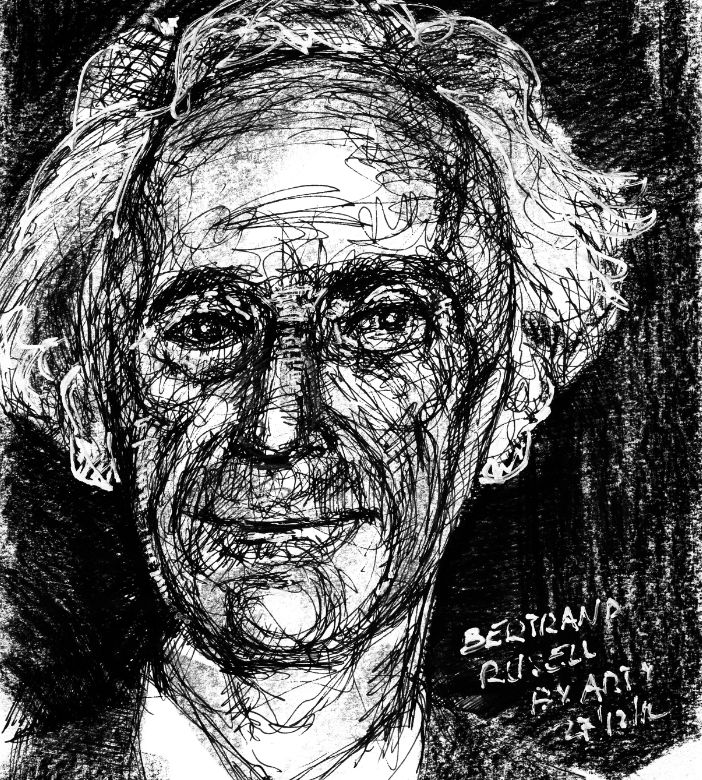

There are two motives for reading a book; one, that you enjoy it; the other, that you can boast about it. Philosopher.

There are two motives for reading a book; one, that you enjoy it; the other, that you can boast about it. Philosopher.