3 Lessons From Hyperinflationary Periods: Reduce Societal Fears

by

September 6th, 2024

Audio Presented by

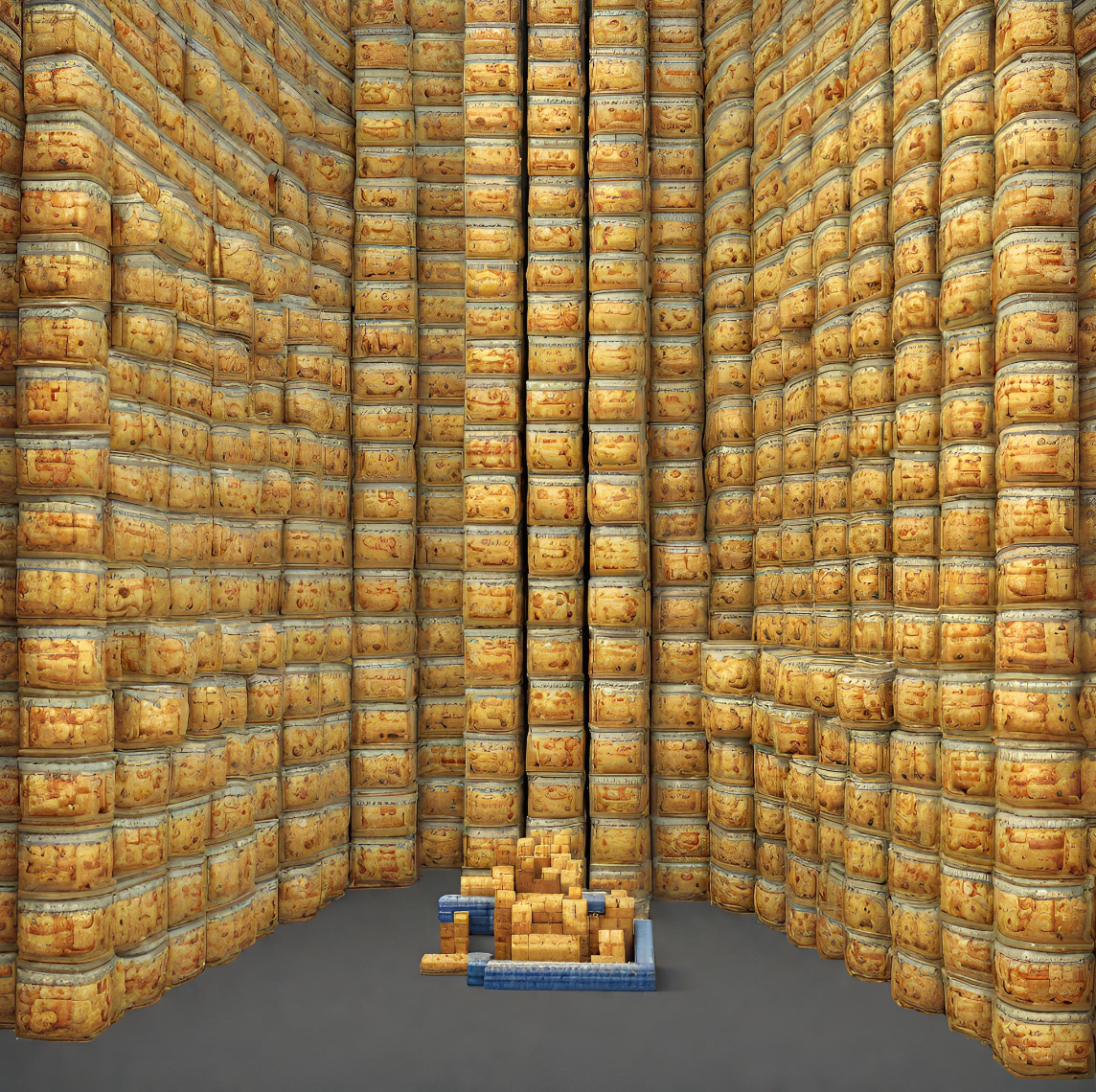

Economic storm warning: Hyperinflation on the horizon, prices skyrocket and purchasing power plummets.

Story's Credibility

About Author

Economic storm warning: Hyperinflation on the horizon, prices skyrocket and purchasing power plummets.